The Fabulous Furry Revolution

The United States has never made a bold move forward without anchoring it in a reading of the past. Our “Founding Fathers” have been carted out regularly to sanctify everything from The Civil War to Progressive and New Deal reforms, the Civil Rights movement to Reaganism. Americans like to frame changes in our politics and culture not as radical breaks from the past so much as realizations of original principles. It is self-evident in our own time. Consider the distance between Lin Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton and the countless founders bios from Fox News hosts. Arguing about America’s future is always grounded in a a declaration about its past.

It should not surprise us, then, that one of the most ambitious projects in the underground comics movement of the 1970s was a cartoon retelling of the war that started it all. The 50th Anniversary reissue of Gilbert Shelton and Ted Richards’ Give Me Liberty: A Revised History of the American Revolution is a cause for appreciation and reflection on the rich legacy of the 60s/70s counter-culture. Across 1975-76 in the pages of their Rip-Off Press comic books and underground newspaper syndicate, the creator of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers and collaborator on the Disney-defaming Air Pirates combined well-researched history with hippie irreverence.

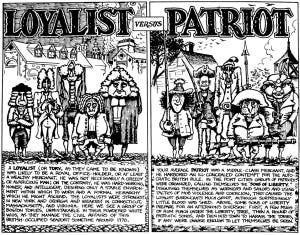

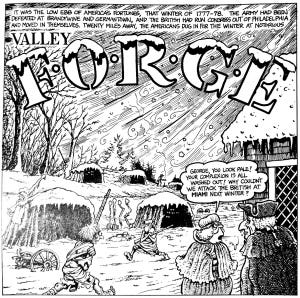

The history is generally firm, if at times zany. The Boston Tea Party, Paul Revere’s Ride, Valley Forge, and Battles of Saratoga, Harlem Heights, and more are all here. As are George Washington, Generals Howe, Gage and Arnold, native American and foreign mercenary conscripts, even Betsy Ross. But so too is the drunken behavior, petty resentments, popular apathy and rampant desertion that lay beneath the gloss of schoolbook versions. This is a warts-and-all “revision” of history. Shelton and Richards (joined at times by Gary Hallgren and Willie Murphy) were using doses of populist realism as well as slapstick to do what underground comics often did best – blend satire and seriousness in ways that the more somber political wing of the 60s did not. There are no glorified heroes in Give Me Liberty. It seemed designed to rebut the romanticized Revolution that Shelton and Richards were seeing at the time in the run-up to the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations.

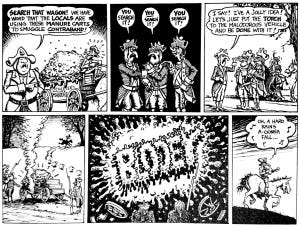

The book is at its best when it blends historic value and comic antics just right. When manure carts laden with contraband arms explode. When patriots save the day on the backs of stampeding cows. When John Paul Jones’ boarding of the Serapis gets a wonderful splash panel that uses slapstick to convey the chaos of war. Two recurring characters keep the story grounded among the grunts rather than just the generals. A patriot newlywed Nehemiah is forever helping the cause in unorthodox ways, like cross-dressing to vamp British generals. And the town lush Ebeneezer is motivated more by his search for hooch than by patriotism.

Give Me Liberty is weakest when it falls into the rut of history-telling rather than showing. The later episodes seem to lose some of the whimsy of the first sections and settle into illustrating the catalog of battles. More than just being uneven (maybe inevitable in a protracted serial project), this rendering of the war is short on the “revolution” part. Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine make brief appearances, but their ideas do not. The conviction behind the patriotism is missing. Likewise, we never really get a sense for what compelled Shelton and Richards to do this formidable work. We know from some of the back matter that Shelton in particular always had a taste for history. He had done earlier work around the Civil War. I would have liked to know more about what he thought he was up to.

And that may even be fitting to this project, which was itself crafted in the malaise and regret of the post-60s, when many felt the counter-culture had failed. As I said earlier, most American change looks for the imprimatur of history. This was true of the 60s as well. Martin Luther King argued that the promise of the Civil Rights movement was not just about justice but about living up to original democratic principles. The Port Huron Statement, which launched the political wing of the student rebellion, the SDS, was grounded in principles of participatory democracy. The back-to-nature and small-is-beautiful movements rejected technocracy and mass consumption in favor of retrieving pre-modern mercantilism and a sense of craft. That impulse to create a usable past can even be seen among the underground cartoonists who helped revive interest in the classic comic strips. Harvey Kurtzman was reprinting Mutt and Jeff and Krazy Kat in his Help! Magazine in the early 60s, and by the end of the decade we were already seeing reprints of Dick Tracy and Buck Rogers.

But by the time Shelton and Richards reconsidered the American Revolution in 1975, they seemed to be finding there less inspiration than warning. In the final chapter of this history, a fallen soldier in the last battle of the war is taken by a ghostly guide through “The Spirit of Revolution” before and after. In this vision, overthrowing autocratic power is just an invitation to new autocrats or mass destruction. Waking from his dream, he declares “’Revolution’ is a vicious circle and an illusion.” Too late, his patriot comrades tell him. They “won” the war.

You don’t need to scratch too deeply to see Give Me Liberty as a dark response to the failures of the counter-culture to effect meaningful change. And you can see reflected in the rest of this Fantagraphics reprint a similar critique of their own generation. In the back end of this volume we get a sampling of Ted Richards’ Forty Year Old Hippie series that depicts the counter-cultural veteran as new age grifter and a stoner without a cause. Of course Shelton’s own Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers was itself one of the most trenchant contemporaneous satires of the very youth culture you would think he should celebrate. But there is the rub with the underground cartoonists of the 60s and 70s, and with art an d politics generally. There was an ongoing tension between the activists and the artists. Straight outsiders would presume they played for the same team. But there was a real, important divide there. More than a few members of the political left in the 60s disliked the antic, comic methods of some wings of the counter-culture, like Abbie Hoffman’s Yippies or Robert Crumb’s tendency to blend weird sex and politics and even mock the humorlessness of activists. It should surprise no one that the America Left has always been thin-skinned about satirizing their own. They always seem to be afraid that someone somewhere (not themselves, of course) will have their faith in the cause shaken by seeing its defenders depicted as imperfect mortals. Having convinced themselves that all art is reducible to ideology, it can only be imagined as weaponry or defense. But as someone who came into a hippie college in the 70s and an elite graduate education in the 80s I can attest that the Sheltons the Crumbs and the Richards helped keep my critical intelligence and my sense of humor alive.