Mickey Mouse Diplomacy: Disney’s Ambassador of American Exceptionalism

By the summer of 1937, Disney’s Mickey Mouse cartoons and the syndicated strip had already become worldwide ambassadors of American mass media. Like Charlie Chaplin in the previous decade, Mickey’s simple visual signature and deft antics translated well from Europe to Asia. The Mouse had effectively displaced The Tramp as an international icon of slapstick. But in August 1937, with Floyd Gottfredson’s Medioka story line, the ambassadorship becomes self-conscious and reflexive..even politicized by both creators and at least one government. Mickey journeys off to the vaguely Slavic kingdom of Medioka to save its corrupt government and oppressed people from feudalism with American ingenuity, empiricism and democratic character. It is the most explicit exercise of the American exceptionalism mythology we are bound to see in comics history, even if it has all of the political subtlety of a Yellowstone episode.

As we have covered before, 30s pop culture was rife with feudal fantasy, the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup to Popeye to The Prisoner of Zenda. And in fact this Mickey tale starts by alluding to the classic Zenda tale that would come to the screen the next month, starring Ronald Coleman. Two “dark foreigners” from Medioka happen upon our Mickey, who appears to be a spot on double for their own profligate King Michael. Their young King is a spendthrift debaucher who is taxing and mortgaging their land to ruin in order to overspend on his own appetites. And so unlike most of the other slapstick monarchies of Depression-era culture, mediocre Medioka is set up as a prime example of a longstanding American trope of the 20th Century – the backward, failing Old World begging for democratic salvation.

After a lengthy kidnapping drama the pun-dipped Minister of Finance Count de Sheckels and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Duke de la Puche explain their plan for Mickey to pose as King Michael just long enough for Medioka to reestablish credit and get on a firmer footing. Gottfredson establishes from the start that this will be a tale of New World democratic character and values against decrepit Old World counterparts. At his first glance into the kind of intrigue and deception bred by undemocratic traditions, Mickey recoils by insisting that “even a King has rights, you know!” And he only agrees to go along when de Sheckels counter-argues that the citizens of Medioka also have rights and that Mickey would be saving millions of “poor people.”

The Medioka saga is remarkable in how comprehensively Gottfredson maps out so many aspects of the mythic American: ethics of fairness, populism and democracy, inventiveness, devotion to fact and frugality – all depicted as endemic, baked into our native character. All of the greatest hits of American exceptionalism are here in snippets of interaction between Mickey and the various figures of Medioka. And at the same time the Disney empire is imprinting this American mythology on Mickey in the same ways Hollywood did in stars like Gary Cooper, Walter Huston, Jimmy Cagney and Jimmy Stewart.

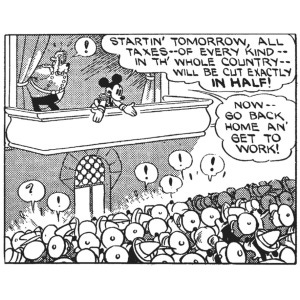

De Scheckels and de la Puche tutor Mickey in the arts of regal disdain for commoners, which our democratic mouse quickly defies by praising the first working stiff these noblemen berate. Likewise, Mickey quickly rejects this scheme to make him a prop for the hierarchical scheme to retain traditional power and finances. He cuts the people’s taxes in half, much to popular acclaim, and then industriously calculates his own more agro-capitalist scheme for a more sustainable economy.

In one of the most overtly political dailies in the series, Duke de la Puche explains to Mickey the principles of diplomacy to “color the truth” in artful ways. Mickey’s progressive expressions of passivity, confusion, disbelief and indignant anger is a case study in Gottfredson’s command of simple shapes to communicate Mickey’s inner conviction and add a richer layer to this fable of American exceptionalism. By the latter 1930s, Hitler’s ambitions to dominate Europe were increasingly clear to some and a matter of open debate. The various diplomatic moves by European leaders carried echoes of the run-up to WWI, the purported “war to end all wars” designed to establish democracy as an inevitable end point of world history. Many Americans felt WWI was a mistake and a failure they didn’t mean to repeat. Diplomacy felt like another relic of failed cultures that left Americans frustrated or bemused. Mickey’s retort to his “lesson” in foreign relations is the very American conviction around plain speech. When he insists in his own folksy vernacular, “And mebbe that is why Medioka’s bankrupt! There’s been too much diplomacy around here and not enough honesty,” he is channeling a broader, deeper critique of Old World culture and statecraft.

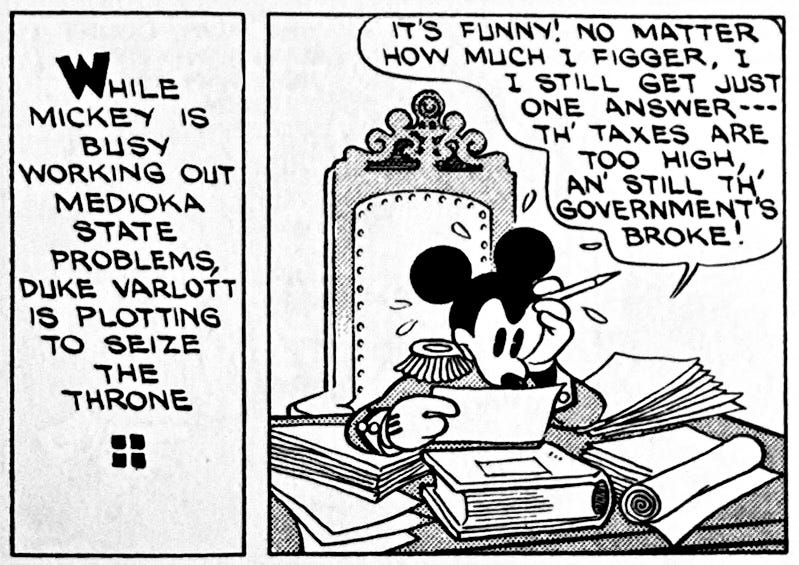

Gottfredson had little occasion in the Medioka story to flex his usual mastery of action, And yet he delivers memorable visuals of Mickey slaving over the books like a small business man trying to find a solution to his cash crunch. The answer is good old middle-American frugality and supply side economics. Lower taxes will incentivize labor. Cutting government spending will balance the books. Halving the military will enlarge the pool of domestic workers. You can too easily parse the politics behind Mickey/Gottfredson/Disney here. But Mickey surely is no New Deal Mouse. To public acclaim, he announces a cut in taxes while in the same breath telling protesting crowds to “go back home an’ get to work.” You can even see foreshadows of Walt Disney’s own attitudes towards labor. Only a few years later, Walt deeply resented a famous 1941 animators’ strike of his studio and subsequent unionization. He openly referred to strikers as “the chip-on-the-shoulder boys and the world-owes-me-a-living lads” and later accused organizers of Communist ties.

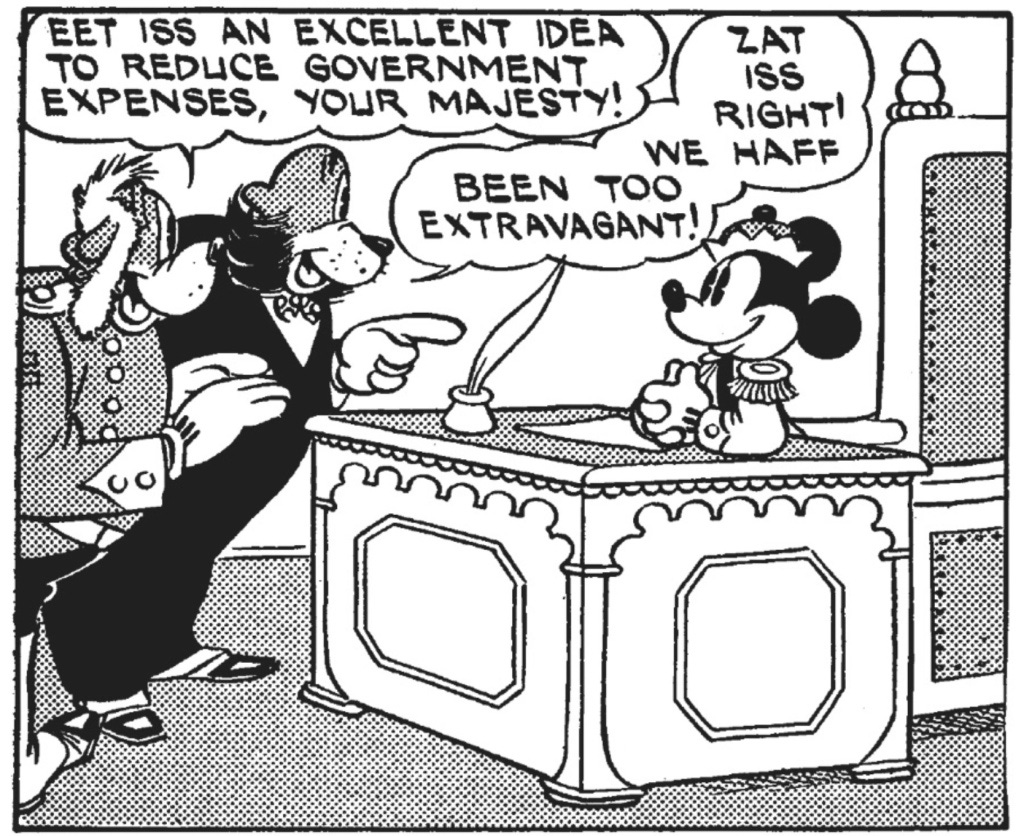

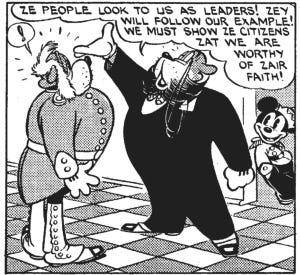

But in Medioka, Mickey’s American exceptionalism is more about democratic character than a firm ideology. He chastises the noblemen for their luxurious salaries and undemocratic disdain for popular will. The aristocracy eventually absorbs Mickey’s own democratic rhetoric, even declaring (albeit pompously) “Ze people look to us as leaders! Zey will follow our example! We must show ze citizens we are worthy of zair faith!”

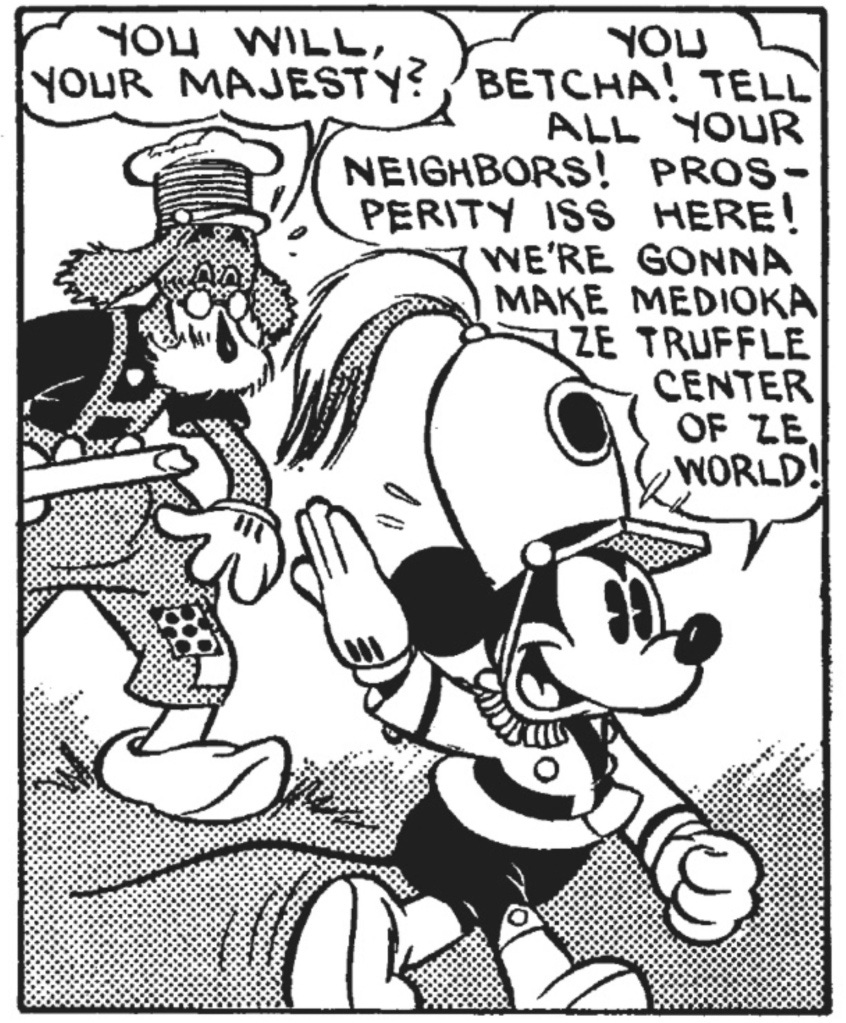

But at the same time Mickey has a bit of American knavery – the personal magnetism of persuasion and a bit of the con about him. He turns the surly crowd back to his side with the largesse of a tax cut he not sure how to pay for. He flatters generals, bakers and noblemen into believing that his scheme will improve their lives, often trotting off in a final panel with the self-satisfied grin of the smooth-tongued Yankee peddler. In fact, if there is a difference between Mickey and other pop populists of the era like Dodsworth or Tom Joad it is smugness. Mickey is not the humble, folksy innocent aborad. He is self-assured, manipulative and even arrogant in asserting his American democratic character and principles onto backward Medioka.

As heavy-handed as the cultural politics become in the Medioka story, Gottfredon eventually makes it more fun than poignant by pivoting his feudal fantasy into one of his more complex screwball sit-coms. When a photographer captures the real King Michael cavorting in nightclubs, the newspaper photo ignites multiple mistaken identity shenanigans. Minnie mistakes the newspaper image for Mickey two-timing her, while the King’s scheming uncle, Prince Varlott, thinks he is a potential body double he can use to replace the “real” king. Meanwhile, the real Mickey needs the real king to return to marry a smitten princess. In masterful Gottfredson fashion, he brings this snarl of conflicting motives and identities together in a madcap clash. After a wonderfully snarled adventure in which Mickey recruits Minnie into trapping the conniving Prince Varlott, the real King Mickey is restored to his throne.

Democracy seems to have won the day, as the King and his court appear reformed, at least for now. When King Mickey arrives for his wedding piloting a humble hay wagon rather than a royal coach, his subjects proclaim, “No king was ever so democratic.” Ultimately, Gottfredson leaves unclear whether Medioka has truly reformed. The Old World may well be hopeless, in this Americanist view. After all, as Mickey has demonstrated, democratic sensibilities are only in part a matter of explicit politics. They are as much a part of character.

The Medioka storyline is notable not only for the unusual bluntness of its cultural politics but for the kind of negative attention it drew abroad. The “royal censor” for the Yugoslavian government banned the strip from the country’s newspapers when they feared that the tale of courtly intrigue and takeover too closely resembled their own situation. The country had a 14-year old king but was being managed by his cousin. The situation escalated when the New York Times writer who first reported the censorship, Hubert Harrison, was deported for reporting on the incident.

As usual, the censors got it wrong. The real challenge of Disney’s Medioka storyline to Yugoslavia and the Old World generally was not in its allusions to royal family intrigue but in the more specific American exceptionalism at the strip’s core. The folksy American democrat abroad was a fun trope of pop culture between the World Wars. But Mickey’s stridency foreshadowed post-WWII American imperialism in all of its arrogant self-assurance in manipulating foreign regimes and the condescension towards other cultures that rationalized it.

But in the context of the 1930s, Mickey’s democratic character was informed by a larger cultural project to understand the uniqueness of American culture. The 1930s witnessed an enormous effort at historical retrieval. In Academia the first interdisciplinary “American Studies” departments and majors emerged, which sought to chart traditions, experiences, literature and institutions that had formed a culture distinct from European roots. There was a great interest in folklore, traditions of oral storytelling, frontier “tall tales,” etc. The New Deal WPA (Works Progress Administration) project included an historical element that researched regional and local history and interviewed many of the last survivors of American slavery. In the comics strips you can see this celebration of a kind of native American genius in everything from plainspoken ethics of Little Orphan Annie and Gasoline Alley to the hillbilly satires of Li’l Abner and Snuffy Smith. In a compact and forceful way. Gottfredson’s Medioka episode in 1937 coalesced many of the themes of an exceptional American character that in many ways was shaped in contrast to the Old World: simple functionality vs. frivolous opulence, plain language vs diplomatic appeasement, self-discipline vs. indulgence, rectitude vs. sexuality, assertiveness vs. subservience, etc. The Medioka episode laid out a simple but comprehensive mythical map of an emerging American self-image that would have both constructive and destructive impact on the world for decades to comes.

Disney vs. The World

The Medioka episode was neither the first nor last time the international regimes questioned the ideological implications of the Disney universe. When the Times writer Hubert Harrison first reported of the Yugoslav ban in Dec. 1937, he recalled an earlier case when Disney caught the eye of Communist Russia.

“In Russia two years ago, Mickey puzzled Communist commentators, who could not understand why he and Walt Disney’s other creations — The Three Little Pigs, Donald Duck, etc. — had built up such a following among the proletariat. They called Mickey a satirical symbol of capitalism, thus: ‘Disney. isreally showing us the people of the capitalist world under the masks of pigs, mice and penguins. It looks like a social satire to us.'”

New York Times, Dec. 6, 1937

In 1938, Italian fascist distator Benito Mussolini banned all non-Italian comic strips on nationalist grounds. Mickey was excepted at the time because Mussolini and his family were fans of the hero, translated as “Topolino” (little mouse). But when Mickey started battling the Nazis once war came, even Mussolini issued a ban.

It has always been easier for non-American audiences to detect the implicit politics of our popular culture output. The first fulsome and comprehensive critique of the colonialist Disney empire, How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic emerged from Chilean American critic Ariel Dorfman and Belgian sociologist Armand Mattelart. The book contended that the apparently benign tales of Duckberg served as capitalist propaganda. While Mickey and friends seemed to most domestic readers benign at best, the implicit “Americanism” of Disney product has always been more apparent outside of the U.S. context.