I Hear America Talking: Stan Mack’s Real Life

Earlier this summer, I got to chat with visual journalist Stan Mack as he launched the indispensable compilation of his most famous work, Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies: The Collected Conceits, Delusions, and Hijinks of New Yorkers from 1974 to 1995. The interview is embedded below with a cursory review after that.

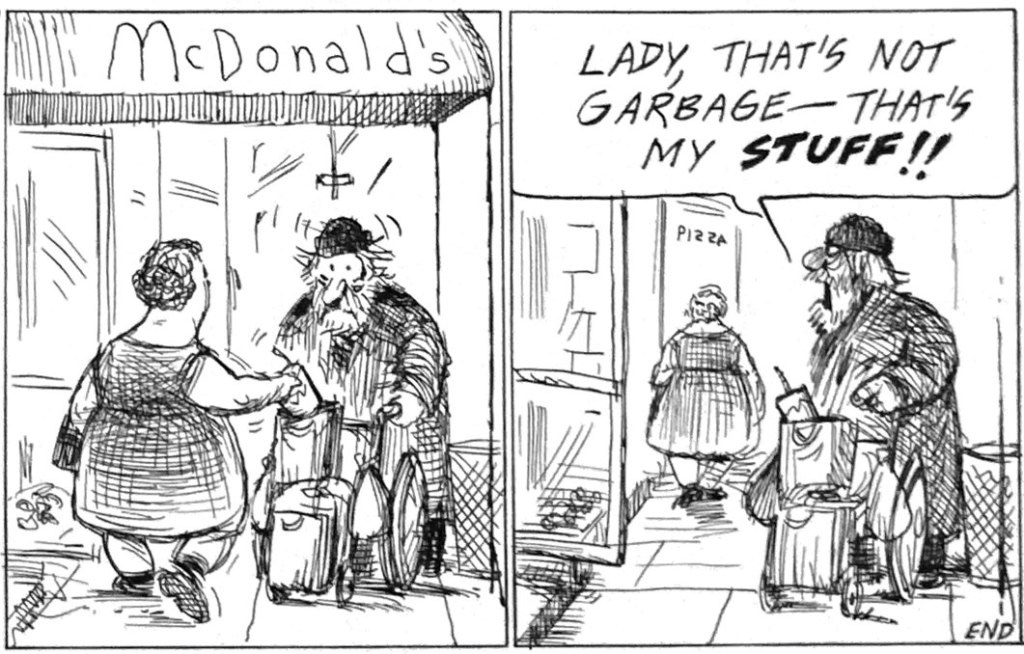

I say “cursory review” because there is no way to do this book justice, and I confess a personal bias. When Stan worked at my longtime haunt, MediaPost, I was on the receiving end of the Real Life treatment. He captured my recollections of being raised by an ad man. I have the subject’s appreciation for the artistry here, his ability to marry text and image, juxtapose verbatim quotes, and shape a narrative arc. And I was a fan from an early age. As a disaffected Jersey suburbanite desperately seeking hipness, the Village Voice was a necessary accoutrement. And Real Life Funnies, that weekly deep dive into the real world conversations and happenings in raucous 70s/80s New York City, was required reading. Each week, Mack went to street protests, trendy therapy sessions, conventions and doctors’ waiting rooms, concerts, park benches and photo shoots in order to record America talking. From gay and women’s rights, gentrification and Reaganism, “yuppie scum” to every imaginable self-help trend, Mack’s book is so vast in its embrace of recent history, I just can’t cover a respectable fraction of it here. The book is a trove of contemporary reportage that is eerily familiar, because so many of the core social, political, personal issues he explored decades ago are still relevant and unresolved.

Real Life Funnies is a kind of bridge between two eras of comics history. It leaned on a long history of illustrated journalism that goes back to the 19th century. The first generation of newspaper comic artists, and even the Ash Can school of American painting, all started as news illustrators. Before newspapers could reprint photographs, artists were dispatched to sketch fires, riots, murder scenes, trials. And leaning forward, Real Life Funnies helped open the doors for much more realistic uses of comic strip forms to engage in autobiography and history. Art Spiegelman’s MAUS, Joe Sacco’s Palestine, Alison Bechtel’s Fun Home all follow in a path Stan redrew for us.

But let me make a few observations that popped for me in revisiting Real Life Funnies. As a visual journalist, Mack has the sociologist’s eye and the satirist’s ear. He goes into a situation, like a residents’ protest against a newly gentrified building, and breaks it down to constituent elements: protesters yelling “Yuppie Scum”, riot police in phalanx formation discussing their next pool party, the self-absorbed yuppie, media chasing arrest counts, the sleeping homeless. But Mack’s prophetic genius was in understanding the performative aspects of all conversation. A true cartoonist, he uses language and image to capture people role-playing, saying things they themselves probably don’t fully believe.

It would be easy to read Real Life Funnies as a kind of removed satire of, as the subtitle has it, “The Collected Conceits, Delusions and Hijinks of New Yorkers from 1974 to 1995.” He has a great ear for the inane proclamation, and so much of the art here is in the voices he captures.

The pomposity of the first year film student: “I’m not pro-oppression but I am attracted to the aura of romance and danger which surrounds the pre-nuclear wars, WWI and WWII. I believe New York is Berlin, 1933.”

The bizarre assuredness of fads: “Now that I am in EST, I can do anything.”

The theraspeak of a “Prosperity Seminar”: “You’re attuned to a Drudge mentality. Come out of that and into a new space.”

The revelations of a maintenance man at the World Trade Center: “All the big shots come down at lunch to smoke dope.”

And of course just the snappy ironic banter of New York that foreshadowed Seinfeld: “One thing you gotta grant the Nazis, they understood leather.”

There is a lot of personal performance in these voices, of New Yorkers playing the role of being New Yorkers. And yet there is a tremendous humanism at the center of this book. Mack is at heart an empath, and Real Life Funnies is also a deep dive into intimacy, the kind of candor that comes from people trusting one another with their mixed feelings and personal resentments.

This Real Life Funnies collection is a welcome reminder of the comic strip’s value as art and as history. It captures aspects of everyday life that elude formal journalism, other forms of art and certainly the historian’s generalizing gaze.