Flesh, Fantasy, Fetish: 1930s and the Return of the Repressed

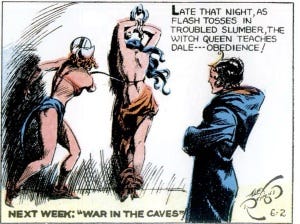

The sheer horniness of the otherwise circumspect American newspaper comics in the 1930s is as unmistakable as it is overlooked in the usual histories. I have written about the kinkiness of 30s adventure in bits and pieces in the past. But rereading Dale Arden’s “obedience training” at the hands of the dominatrix “Witch Queen” in Flash Gordon, reminded me how much unbridled fetishism romped through the adventure comics of Depression America. Any honest history of the American comic strip really needs to have “the sex talk” about itself.

I tripped over this masterful femdom panel while researching an upcoming piece on women-led kingdoms in 30s adventure. It reminded me how often I have written about the barely veiled eroticism of 30s adventure. Following the lead of pulp fiction, the great adventures of the 30s – Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, Prince Valiant, The Phantom, Terry and the Pirates, Tarzan, Li’l Aber, etc. – got away with all kinds of cheese and beefcake art, even fetishistic kink.

But let’s review. Alex Raymond was the master of erotic heroism on Sunday newspaper pages. As I outlined here, Flash Gordon’s celebration of human flesh knew no bounds. Men and men, men and women, heroes and villains – no one on Planet Mongo kept their hands to themselves. As in most adventure strips, the fantastic latent sexuality of our male hero is the animating force. From the first episode, princesses, villain and ally queens compete with the hapless Dale Arden for his affection. And artist Raymond’s apparent love of all human forms builds a homoerotic world that could carry a range of subtexts to diverse readers.

No one seemed to understand the ambiguous erotic potential of cartoon art better than Brick Bradford’s artist Clarence Gray. The adventure hero Bradford never achieved the fame in his native land that he did abroad, in part because its distribution via King Feature’s subsidiary syndicate Central Press Association focused on small town outlets. But Brick had a worldwide following that kept it alive from its launch in 1933 until 1987. Like Flash, he was a blonde athlete-turned adventurer whose flesh and muscularity played lead roles in the strip’s visual appeal. And Gray loved depicting buttocks, a lot of male bonding and engaging in some visual double entendre that are hard to believe were accidental.

Milton Caniff’s mastery of art and story found light erotic marriage in his occasional striptease recaps. His slow disrobing of fan fave femme fatale Burma (who apparently prefers sleeping au naturale) ends in a deliciously inked kicker panel. As Burma thinks out loud, her disinterest in her own nakedness and your ogling makes this even more effective than a tease.

Arguably, Prince Valiant’s Hal Foster drew sexier medieval landscapes and architecture than he did alluring bodies. And yet he seems to have occasionally pushed the boundaries of acceptable nudity in strips farther than anyone else on the Sunday page. Val and his merry warriors may have missed home and wives, but they apparently revel in group baths. This gave Foster the opportunity to literally hide the sausage in creative ways.

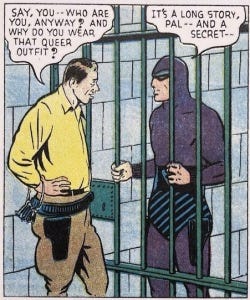

But the king of kink among 30s adventurers had to be Lee Falk and Don Moore’s The Phantom. Famously, “The Ghost That Walks” pioneered the skintight hero’s costume, which, like body paint, somehow made a sort of public nudity passable in the emerging comic book world. Generations of adolescents of all sexes salute your genius for repression Mssrs. Falk and Moore. It comes as no surprise, then, that the strip that let superhero fans have their sex and innocence too, was a fetishist’s dream. The Phantom was himself bound, imperiled and tortured regularly…and well, especially by villainesses who couldn’t decide if they wanted to beat him or bed him. And The Phantom gave as good as he got, often vamping his femme fatales when necessary and delivering spankings as needed. And to artist Moore’s credit, he didn’t need flesh to surface a woman’s sexiness. He had a fashion illustrator’s appreciation for draping and form-fitting gowns that made a woman’s body more titillating when dressed. Every first generation comic book artist followed Moore’s lead in making the full body leotard the superhero convention. But few seemed to have grasped the fetishistic potential here.

In fact, the 1940s comic book descendants of the pulp and comic strip generally missed out on the critical kinky trope of 30s heroism – the dominatrix. I will explore the queen bee character more in the upcoming project on fantasy matriarchies in 30s comic strips, but the sexual dimension is worth a mention here. The decade’s funny pages were awash in evil queens, vindictive princesses, morally ambiguous adventuresses, sadistic girl gang leaders and more. It was as if the hypermasculinized new hero demanded a villain that was opposite him both in morality and gender. They bound, beat, betrayed, humiliated and imprisoned our heroes with relish. But, of course, they usually loved him as well.

The 1930s were pivotal in the evolution of the American comic strip. Standard histories focus on the rise of the serial adventure format in these years: Flash, Terry, Valiant, etc. This is not entirely true, of course. Roy Crane’s Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy, let alone Harold Gray’s pint-sized picaro, Little Orphan Annie, Frank Godwin’s elegant adventuress Connie, and even Bill Conselman and Charles Plumb’s Ella Cinders pioneered the conventions of extended continuity strips in the 1920w. The 1930s are more accurately seen as the period when the comics started reorganizing their content around the genres that were also shaping fellow mass media like film, radio and magazine fiction. Sci-fi Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon), mystery (Agent X-9), westerns (Red Ryder), third-world adventuring (Terry, Jungle Jim, Phantom), even the first inkling of the soap opera (Apple Mary) came to the comics page. Previously the medium relied most heavily on physical comedy (gags and pranks) and domestic situation comedy, a format it helped invent (covered here and here). The 30s represented the comics page aligning with the rest of an evolving mass media industry and consumer culture generally. Genre helps organize commercial fiction as a consumer product, satisfying market expectations with predictable, repeatable formulas. And with the pulp and film genres came one of their most important marketing lessons: repressed sexuality makes for great commercial art. Raymond, Caniff, Falk/Moore seemed to understand what the pulps already knew all too well. All manner of sexual allusion could be neatly packaged in the guise of action and adventure.

It is ironic that this explosion of kink in adventure comics occurs when other parts of American pop culture, and even other comics, are retreating from excess. As the full force of the 1929 stock market crash swept down from the investment class and far beyond Wall Street, the first cultural responses were mixed but extreme. The sexual openness of flappers, closed cars, heavy petting and partying that typified a “Roaring” 1920s extended into an explicitness to early 30s Hollywood talkies. This was the infamous “pre-code” era of near nudity and sexual inuendo. Likewise, real and fictional gangsters like Al Capone, Scarface, Bonnie and Clyde became romantic folk heroes as people tired of Prohibition and the hypocritical corrupted legal institutions that maintained it.. At the same time, political extremism flourished as both capitalism and democracy itself no longer seemed inevitable. At midpoint in the 1930s, however, moderation and backlash sets in. Complaints about the levels of violence, sex and disrespect for authority move Hollywood to tighten and enforce its decency rules (The Hayes Code). FDR’s New Deal mollifies and moderates many on the extreme left away from outright Comunism. And FDR haters like radio priest Father Charles Coughlin veer to the margins with a shrill anti-Semitism that seems closer to Euro-fascism than American populism. Even the above-the-knee flapper hemline famously crashed to ankle-length day dresses and floor-length (but clingy) evening gowns. A new conservatism is evident even among comics syndicates, as strips like Dick Tracy and Radio Patrol were self-consciously designed to de-romanticize crime and buttress traditional legal institutions.

The heroic adventure genre that flourished in the 30s was a part of this retrenchment. It extended to the comics pages the escapist response to The Great Depression in Hollywood (musicals, romantic and screwball comedy). But at the same time it found a socially acceptable channel for the sexual and violent urges that otherwise exploded earlier in the decade and were being actively repressed in American culture. The campy kinkiness of Terry, Flash, Val and Phantom was a kind of revenge of the repressed.

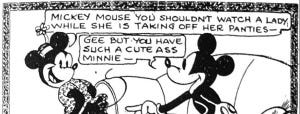

And it is a little hard to believe in retrospect that editors, artists and most audiences weren’t all in on the game. After all, one of the most important and popular comics genres of the 1930s flourished because they gave these comic characters the active and unrepressed libidos most readers already imagined for them. Can it be coincidental that at the same time repressed sexuality is at its height in the newspaper comics, the pornographic Tijuana Bibles reach their peak in distribution? Pop culture critics like to characterize marginal and extreme bits of media like the porno 8-pagers as somehow “subversive” or “transgressive” rejoinders to mainstream sensibilities and structures. Are they, though? When the mainstream culture they purportedly “transgress” is already doing half of the work for them?