Buster Brown: ‘Race Suicide’ v. Family Planning, Circa 1903

Talk of declining fertility and birth rates, even white nationalist mumblings about “race suicide” have become a weird sidebar this election cycle. At the turn of the 20th Century, all of these themes had already been well rehearsed. In 1903, R.F. Outcault’s blockbuster hit Buster Brown alludes to contemporary arguments around changing gender roles, women’s increased autonomy, family planning and, yes, “race suicide.”

When Buster Brown launched in 1902, it was the beginning of a pivot among American newspapers towards upscaling their cartoon offerings. Outcault, who had pioneered the serial comic strip character only six years before in the Yellow Kid, was going middle class, focusing on pampered cherubs of the suburban parlor rather than urchins and toughs of the city street. He was following the market. Newspapers chains and syndicated strips were starting to expand quickly into smaller cites and suburbs, which itself helped make the comic strip the first true “mass medium.” For the first time, readers in many major cities and on both coasts were experiencing the same piece of entertainment simultaneously, the geginings of a nationally shared media experience. Publishers needed to broaden their appeal from the city tabloids that spoke to a heterogeneous emigre audience and to a broader national audience dominated by an emerging white middle class. Cartoon mayhem would continue in Outcault’s new setting, but it was framed as boyish misbehavior and healthy male prankishness – nothing that a good spanking and a mea culpa couldn’t solve. Buster’s antics are on a par with the Katzenjammers, but they inevitably end with his written “Resolved!” declaration about the error of his ways.

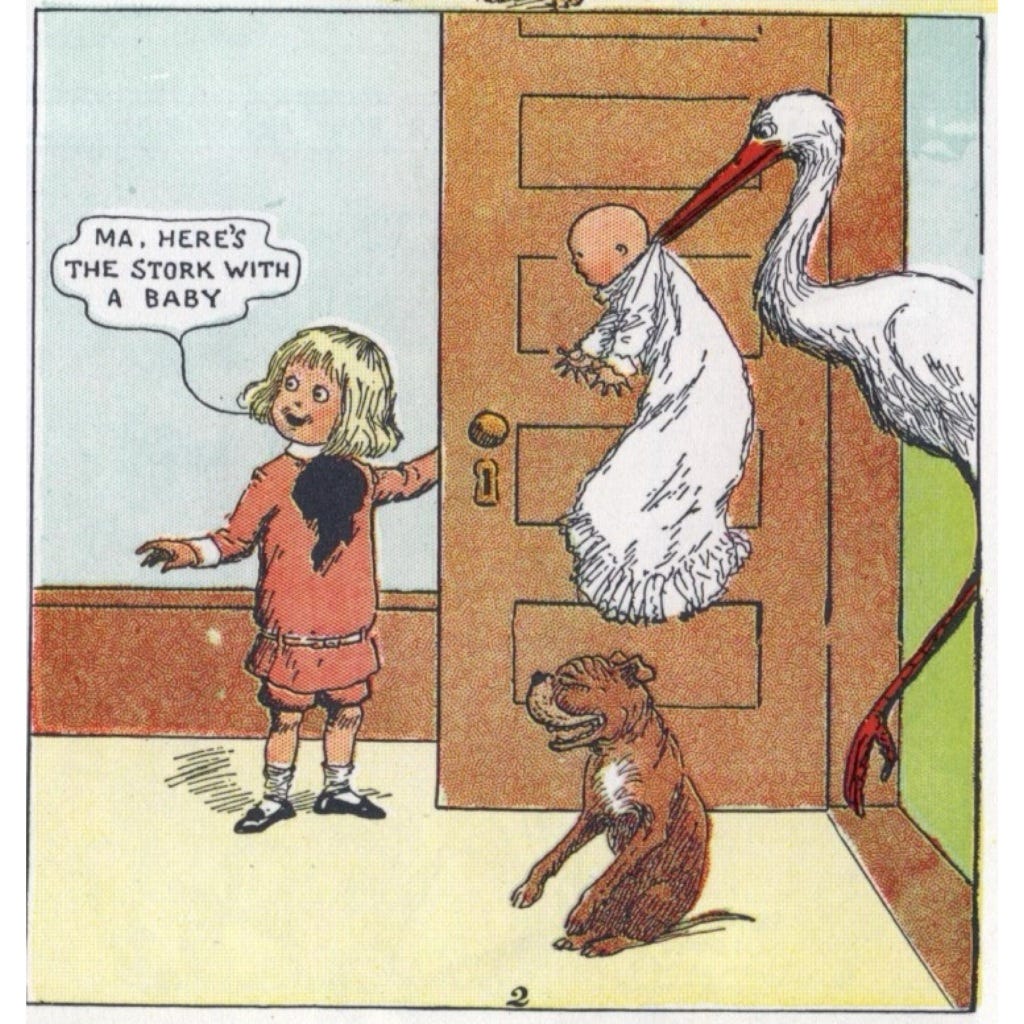

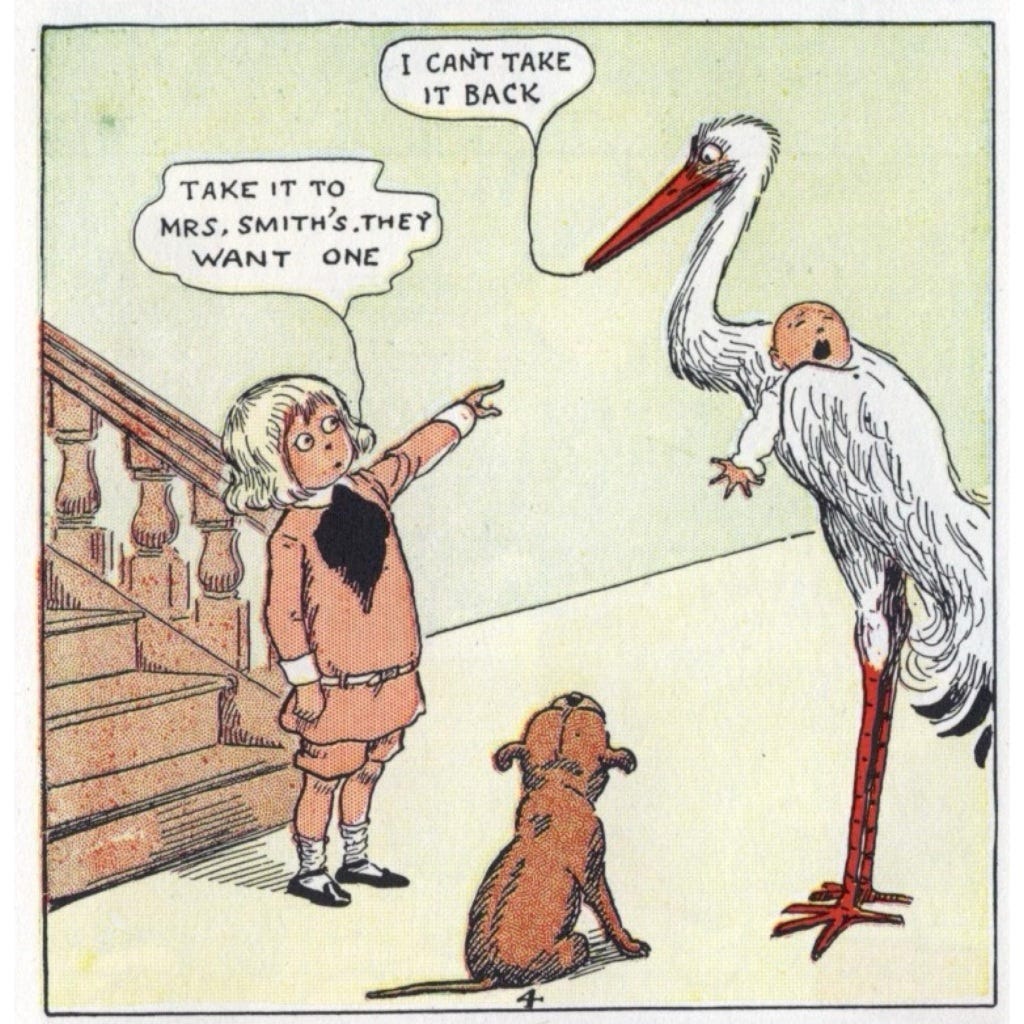

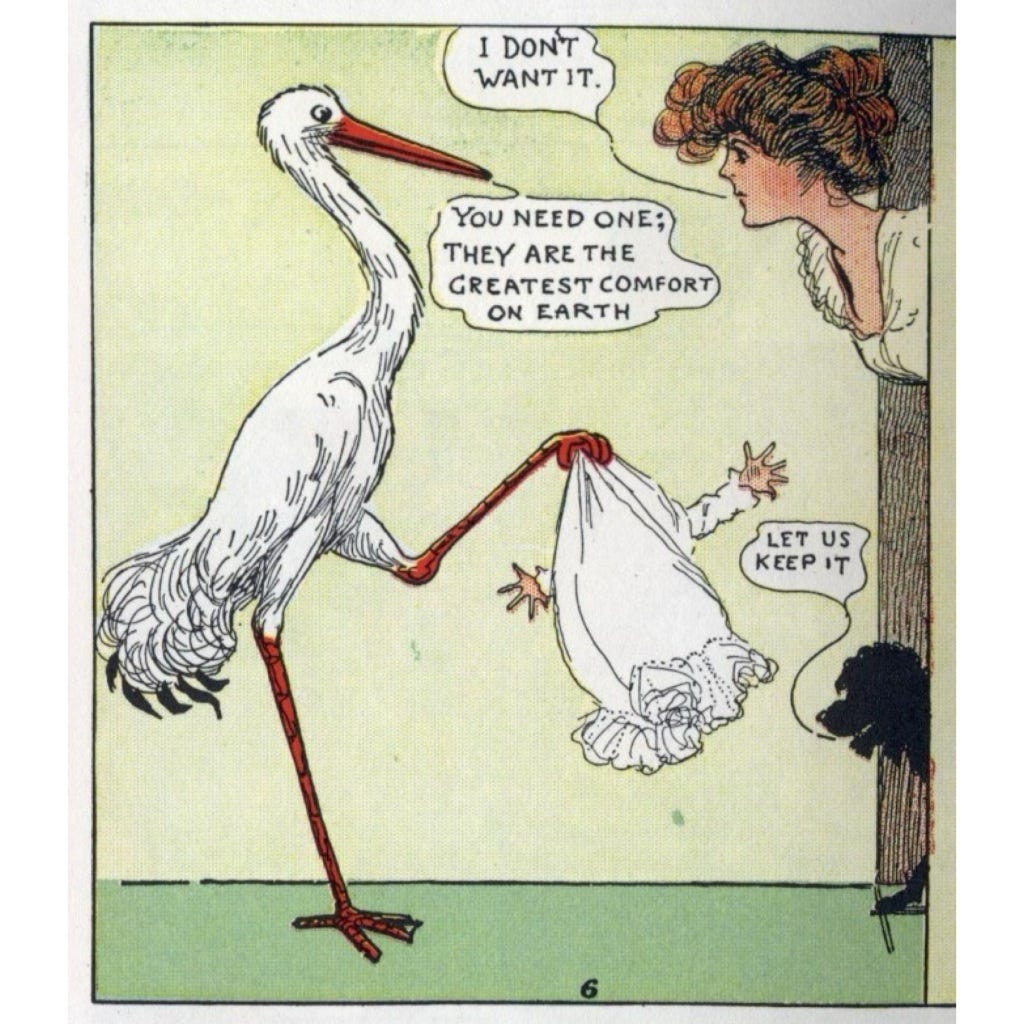

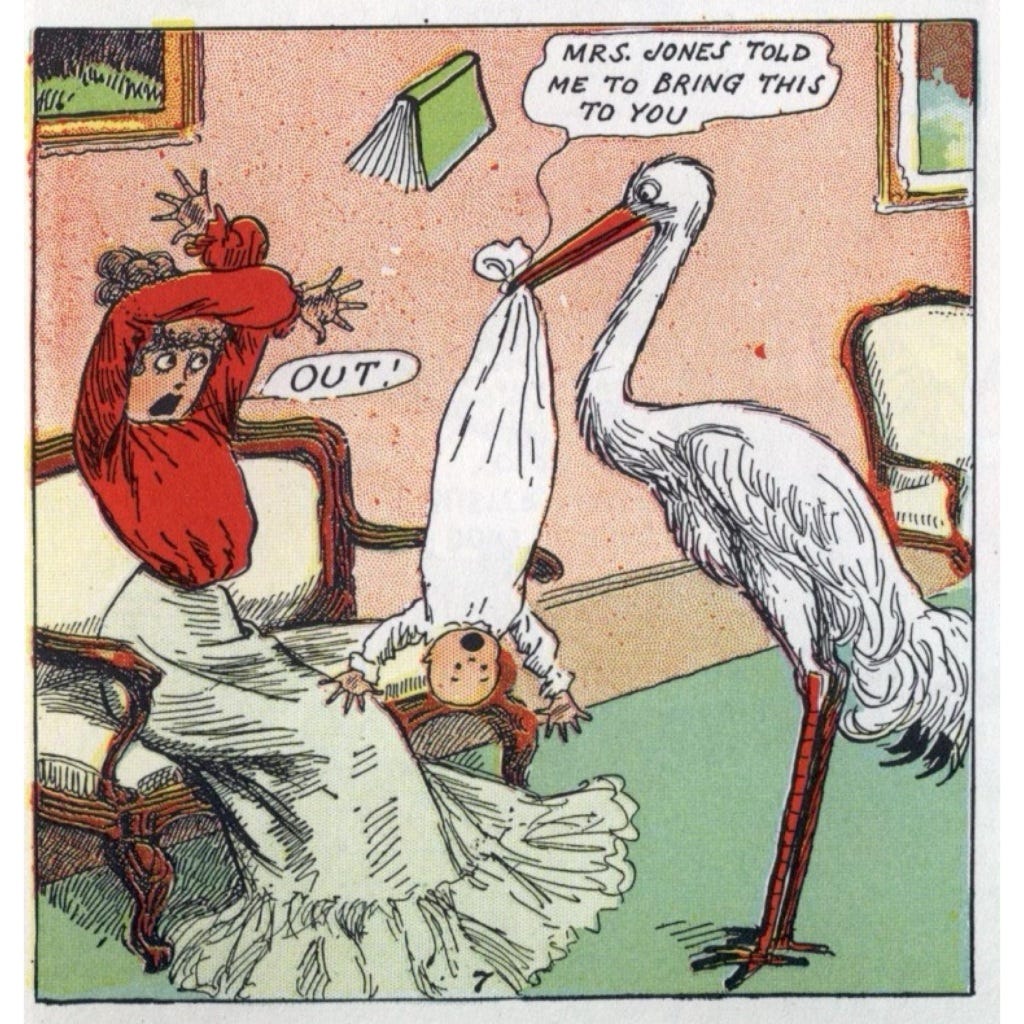

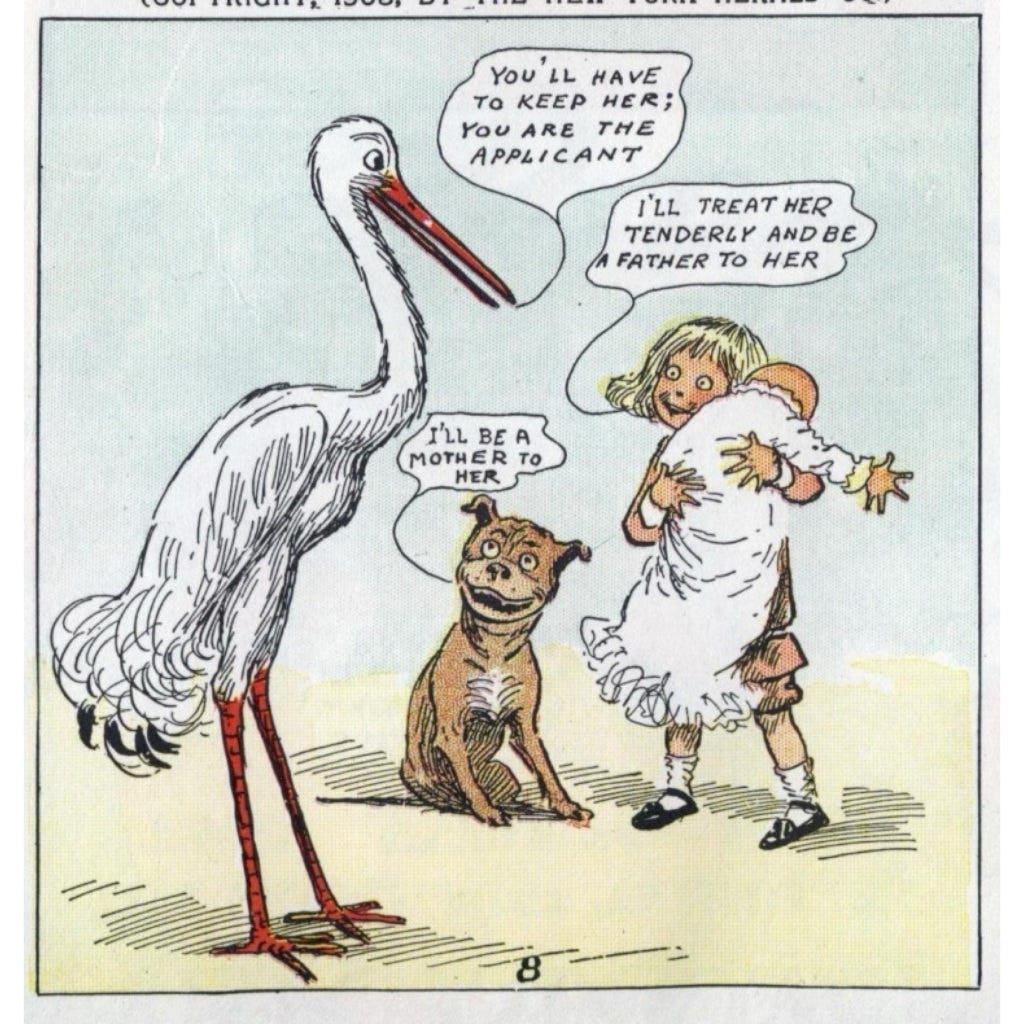

But in this wonderful July 26, 1903 episode, Buster disrupts the new middle class America in a deeper way by recruiting the stork to deliver him a baby sister. Mrs. Brown and all of the other mothers in the building turn away with increasing horror this feathered baby pusher, leaving Buster and Tighe to become “mother” to an unwanted foundling. The issues at the heart of this strip are profound and serious, even if Outcault’s wit is sharp. Buster’s usually devilish role is reversed, as he plays the naif who is oblivious to the practicality of family life. The stork is essentially a baby salesman here, claiming he can’t take the baby back and trotting out unscrupulous appeals to maternalism. “They are the greatest comfort on earth,” he argues to a resistant mother. And from panel to panel, he treats the baby itself with greater disinterest as it dangles from his beak. The terror of the moms crescendos with one mother shrinking from the stork (“OUT!) as if from a vampire.

This is a genuinely witty take on multiple strains of popular American thought at the time. A new generation of women were asserting themselves into the public sphere in many ways; some as careerists, some as reformers and political activists (suffrage, temperance), and others just exercising greater authority in the home. There was predictable resistance to these trends, with critics as noteworthy as Theodore Roosevelt arguing in 1906 that families rejecting “the supreme blessing of children” were not only guilty of “coldness”, “self-indulgence” and “viciousness” but were imperiling white America with “race suicide.”

Outcault and Buster are not explicitly denouncing Mrs. Brown and her neighbors as coldly indulgent, and you could see the mother’s responses as an early defense of what we now call “bodily autonomy.” But his final resolution surely seems to veer into the realm of J.D. Vance’s screeds against childless cat ladies. “GOODNESS!!! What are we coming to?” It is an old story in American history when issues of immigration pop into the main lane of politics. Threatened incumbents stoke fears around the supposed fertility of incoming (typically non-WASP) groups, racial “replacement” and the end of civilization. Cultural historian Lara Saguisag contextualizes this strip and the race suicide argument well in her excellent 2019 book Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2019), pp. 147-149). She argues, “there is no question that the episode primarily means to admonish women who emphatically declare ‘I don’t want it” and who refuse to fulfill their so-called natural and national duty to procreate.” (Saguisag, p. 149).

Well, maybe. As much as I admire some of the cultural history emerging around early comics in recent years (and Saguisag’s in particular), there is a tendency for historians to reduce popular culture to ideologies and arguments that miss the complexities of artistic expression. Like much of American newspaper comic strips in the first decades, Buster Brown was dripping with irony, ambiguity, ambivalence in depicting turn-of-the-century America. To argue, as some do, that the antics of Buster, the Katzenjammers, Happy et. al. represented a “subversive” or “anarchic” subtext to these early comics is just as reductive as arguing that their final panels (a spanking, an arrest, a resolution) reassert some sort of “middle class social status quo.” Both are true (and more) all at once because that is what effective art does in a culture. It allows for cultural play, engaging ambiguity, extending arguments and feeling to absurd lengths in a sandbox without consequence. Outcault’s strip is a good example. It engages a serious, even grim, issue in American life with fantasy, satire, burlesque excess that can be read in multiple ways. Whether we believe that Buster’s final resolution is a genuine expression of Outcault’s views on “race suicide” and a supposed decline of maternalism is beside the point. Regardless, the preceding panels carry multiple meanings. The stork is a cloying baby marketer. Buster is a sentimental naif. The moms are equally unsentimental and steadfastly un-maternal. But ironic remove blankets all of Outcault’s work. Buster’s weekly “Resolved!” is mock moralism. It is obviously disingenuous, because we know Buster will (must) play the bad boy next Sunday…and he knows it too.

This, like many comic strips of the era, was both of and apart from the newspaper experience that contained it. Light-hearted as the comics may seem, their roots were journalistic. The first generation of cartoonists at the major newspapers handled a range of art tasks, including news assignments to illustrate everything from disasters, murders, trials and fires to fashion and politics. They were newsmen. Outcault himself got inspiration for Hogan’s Alley as well as other urchin cartoons from walks in the New York ethnic neighborhoods and tenements. The comics were topical, sometimes obliquely in depicting city types and streets, and sometimes directly in alluding to current events and trends. But their unique role was to recast the topicality of the rest of the newspaper into different form. Most often they offer a posture of wry remove, a way of engaging familiar sources of social argument and anxiety, in a way that lets us contain and frame, even diffuse the tension, of the very things that concern us. It is serious because of its un-seriousness. It gives us a place to play with our own culture.